Dear Friends,

Wow, that was fun! Last week I asked you to share something you had to memorize in your school days, and I got so many responses: here, via private email, and even one on Facebook Messenger.

Every response is so very welcome. Thank you.

Our memory work enjoys quite the range, let me tell you. We range from scripture to children’s poetry about goops, vultures, and spaghetti (three different poems, all about eating, can’t say why). One poem earned its reciter (S., in the 1st grade) a blue ribbon. Another poem earned its reciter (B., senior year of college) a bride (me).

(Truth be told, Bill didn’t have to memorize Shakespeare’s 116th sonnet. He did it because he wanted to, because he wanted to impress me. And his memorizing it didn’t turn instantaneously into a wedding, but it certainly helped.)

The readership here— based on what was shared, anyway— reveals us to be quite the culturally literate group: E. memorized several of Shakespeare’s sonnets and some of Donne’s. R. memorized the prologue (in Middle English, of course) to The Canterbury Tales. And one of my readers (P.) actually memorized both Portia’s “quality of mercy” speech and Shylock’s “I am a Jew” when she was in high school.

Several also expressed appreciation for having Psalm 23 memorized. Another (M.) knows all of Romans 12 by heart. And O., like me, knows (and loves) Psalm 103.

Interesting fact: no one responded with regret. Everyone seems to be glad of what they were made to memorize, or decided to memorize on their own.

Well, okay. There is one. M. said she wishes she could get the spaghetti poem out of her head. I have no idea how to help her with that.

You may recall the point of all that— which is that I’ve been thinking about words and the sounds they make, how their sounds can help us grasp their meaning. Onomatopoeia is the most obvious example (and for the record, “onomatopoeia” is very fun to say, and you should say it, now, to yourself very quietly. See? Also, maybe to try another time, are “onomatopoeic,” and “onomatopoeically.” These, also, are a good time). You remember onomatopoeia from language arts in fourth grade. It’s when a word sounds like the sound it’s describing. You know, like fizz, or bang, or whisper.

But meaning in the sounds of words goes well beyond this, and sometimes we have to pay attention to see just exactly how the two are connected.

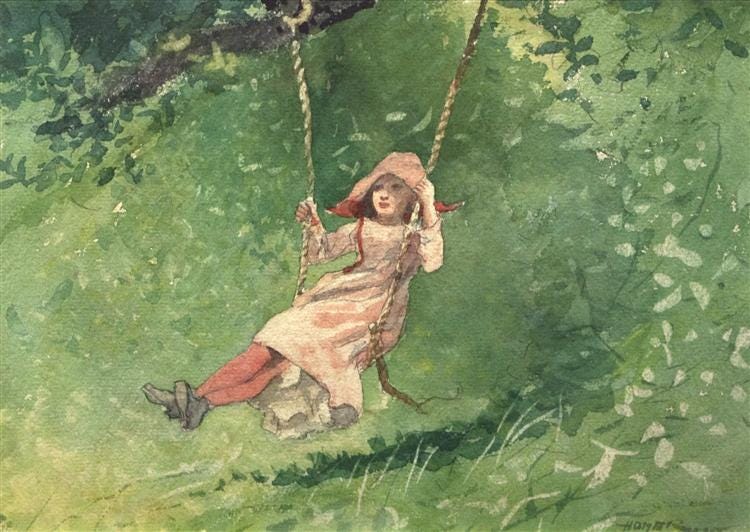

I didn’t realize it all that much myself until I was explaining it to someone else. That’s what happened to me several years ago with a poem by Robert Louis Stevenson. A friend, whose daughter was memorizing and reciting a poem, texted to ask me if I thought the sound of the poem was getting in the way of its meaning.

I wrote back to her, and then I did some more writing myself. I’m sharing that writing with you here:

Two Questions

The text had two questions, the first from the daughter, who is ten:

“Are you related to Robert Louis Stevenson?”

And the second from the mother, who is old enough to be a mother:

“(The Daughter) is reciting her most favorite tomorrow… ‘The Swing.’ I’ve been coaching her to try to recite it without the cadence because I think it loses meaning. Thoughts?”

Thoughts. Immediate: to swings, and how I love to go up in them.

How do you like to go up in a swing/Up in the air so blue? Oh, I do think it the loveliest thing/ever a child can do!

I’m thinking of the time I learned to pump the swing myself. We were visiting my grandmother in Florida, and my older sister and I were taken by the hand by our father and walked rapidly (my father always walks rapidly) down a sidewalk that had, to one side, a tall white fence. Over the top of the fence we could see lemon trees, and my father sang us a song about them as we went.

Lemon tree, very pretty and the lemon flower is sweet. But the fruit of the poor lemon is impossible to eat.

And this was very funny, because my father loves lemons.

We arrived at a park, and my father pushed us on the swings, and then he explained how one leans on a swing and pushes one’s legs out and back again. Suddenly I had learned to pump the swing with my legs, and I could swing on my own.

How do you like to go up in a swing, up in the air so blue?

I pushed William on a swing when he was barely old enough to sit upright. Everett, too. And when Emma turned one, we bought her a baby swing for the swing-set in the back yard. I remember her blond hair, so fine and straight, swaying back and forth from its pigtail above her grinning face.

The mother: “I’ve been coaching her to try to recite it without the cadence.”

Thoughts?

Yes, to the mornings my children and I sat around our kitchen table eating breakfast and reciting poetry. It was my way of packing in a few elements of school before they had a chance to realize it: a Bible story, a picture study, a poem over pancakes and in our pajamas.

Among the many, we learned Stevenson’s “My Shadow,” “The Wind,” and “The Swing.”

“Are you related to Robert Louis Stevenson?” I think my children wanted to know if they were, too.

Thoughts?

Yes, to grading papers at my desk when teaching high school, typing paragraphs of encouragement about supporting arguments and placing commas inside (INSIDE) the quotation marks, and wishing from time to time that these students had spent a small corner of their childhoods reciting poetry–and many of them had. Because you can teach a person how to shape an argument, how to develop said argument over a series of paragraphs, how to enfold supporting evidence via quote or paraphrase into one’s sentences. But by the time one is in high school, it might be too late or insupportable to teach the value of rhythm, the power of varied sentence length, the priceless weight of emphasis and inflection, the music of our spoken–or written–words.

The mother: “I think it loses its meaning.”

Can it?

Up in the air and over the wall/till I can see so wide/Rivers and trees and cattle and all/Over the countryside.

I can imagine the daughter standing at the corner of the sofa, reciting. Or seated at the table, head bent over her coloring, reciting. UP in the AIR and Over the WALL till I can SEE so WIDE.

What is the rhythm of this poem if not Stevenson swinging himself? Back and forth, back and forth. The daughter may be sitting at the table, colored pencil in hand, but the words she is saying are motion, and they are moving her back and forth with the poet himself, with all children anywhere ever who have sometime swung on a swing.

Till I look down on the garden green/Down on the roof so brown

Stevenson’s poem will lose its meaning only when there are no longer children outside because they’ve all turned to their iPhones, when all the swings sit idle, when the rushing breeze and flying force born of a child’s effort loses all power to answer.

Up in the air I go flying again/Up in the air and down!

“Thoughts?”

Yes. That surely some of the meaning is lost on the daughter, for whom swinging in this way is so close–for now–to her everyday experience. For her, for now, this mother is doing everything right: getting this poem in the child’s head. It’s Stevenson’s cadence that will keep it there, and so she’ll be saying it in her head for years to come.

And someday she‘ll be pushing her little one on the swing and admire how the breeze pushes that one sweet curl back and forth, and she’ll mindlessly start saying the poem to her curly-headed cherub. And suddenly the poem’s meaning will bring happy tears to her eyes, just because the realization is so sweet, and she’ll know for the first time that her mother gave her that poem–a gift– years ago, and she’s only just opening it now.

“Are you related to Robert Louis Stevenson?”

Yes. We think so. Scotland is small enough. How many Stevensons can there be?

“Mom, are we related to Robert Louis Stevenson?”

Sure. Why not?

That’s almost all for this time. Just two things.

Our question for this week. Are you related (however far-distantly) to anyone famous? If so, whom? and

For reason of future publishing efforts, I’d very much like to broaden the reach of this newsletter. If you know someone (or ten-ones, or twenty?) whom you think would enjoy this newsletter, would you kindly share it with him? her? them? Thank you in advance.

And thank you, as ever, for reading.

With joy,

Rebecca

Oh my word. I didn’t get the “are you related to Robert Louis Stevenson” question until the very end. Your last name. 🙄

To the defense of this mother: are we sure she knew what cadence is? Otherwise— honestly!! Did she want her daughter to recite like a robot?

I do love that poem about swinging!!

I am related to someone famous in American history: he was William Brewster and he was the pastor on the Mayflower. Most people (of the people with whom I share this information, and honestly the subject doesn’t often come up) claim to recall the name from history class, but sometimes I wonder if they really do. I say all that bc he maybe isn’t so famous.

Thank you for this newsletter. I really enjoy it!! I will share it again and with more people.