Did you make any New Year’s resolutions?

I don’t think I’ve made any in years. I recently learned that this isn’t uncommon: apparently, the lion’s share— 49%— of resolutions at the year’s turn are made by people aged 18-29; while only about a fifth of folks my age make them.

I wonder why that is. Have we arrived? We don’t tend to make resolutions because we don’t need to? Maybe my age bracket consists of people who have reached our prime in terms of age and also, somehow, our prime in terms of meeting ambitions.

Sounds good.

Or maybe we don’t tend to make resolutions because we’ve been down this road a time or two already and we know how it goes. I only learned a week ago that Quitter’s Day is a thing, which makes sense and also seems kind of sad.

No, I don’t make resolutions, but I like the concept. What’s a resolution if not evidence of hope? Yes, resolutions get broken quickly enough— but that’s due less to impossibility and more to other things. Quitter’s Day as an official calendar item feels every bit of cynical, mocking, misanthropic.

That’s a lot of negativity so early in a new year.

Do you think “misanthropic” here is too strong a word? I don’t. IF it’s in the nature of human beings to become, to look for and pursue ways to improve, to continue as long as they’re living to develop and grow, then Quitter’s Day might indeed be misanthropic.

It is, at the very least, unhopeful.

Or. OR. Maybe I’ve misunderstood. Could be Quitter’s Day is meant as motivation: a way to encourage resolution-makers to keep going. If you’re sticking to your resolution commitments beyond Quitter’s Day, then already— even before mid-January— you’ve accomplished something.

I hope that’s it.

But this newsletter isn’t about resolutions or Quitter’s Day. It’s about the beginning of an exploration in this space of identity and joy. I mentioned last time that, in 2025, I hope to complete a draft of my next book, expanding my dissertation on Kierkegaard’s The Sickness Unto Death. Key to understanding his book is one of Kierkegaard’s fundamental observations about human beings: we are in a constant state of becoming.

This state marks a difference between us and all other animals. While a kitten becomes a cat, a puppy becomes a dog, and a zoea becomes a megalopa becomes a juvenile becomes a hermit crab, these creatures cease developing beyond the adult stage. Yes, some can be trained in various ways, but this is the result of— ahem— training.

Humans also reach the adult stage, but they never cease becoming. This is because, Kierkegaard’s explains, “The human being is a spirit.”1 We’re not only physical matter: ligament and muscle, organ and tissue, neuron and synapse. We’re physical beings and spiritual beings, and the spiritual being continues to become for our entire lives.

I realize I’ve given you little new information about Kierkegaard’s thinking in this newsletter, but never fear: there’s more to come!

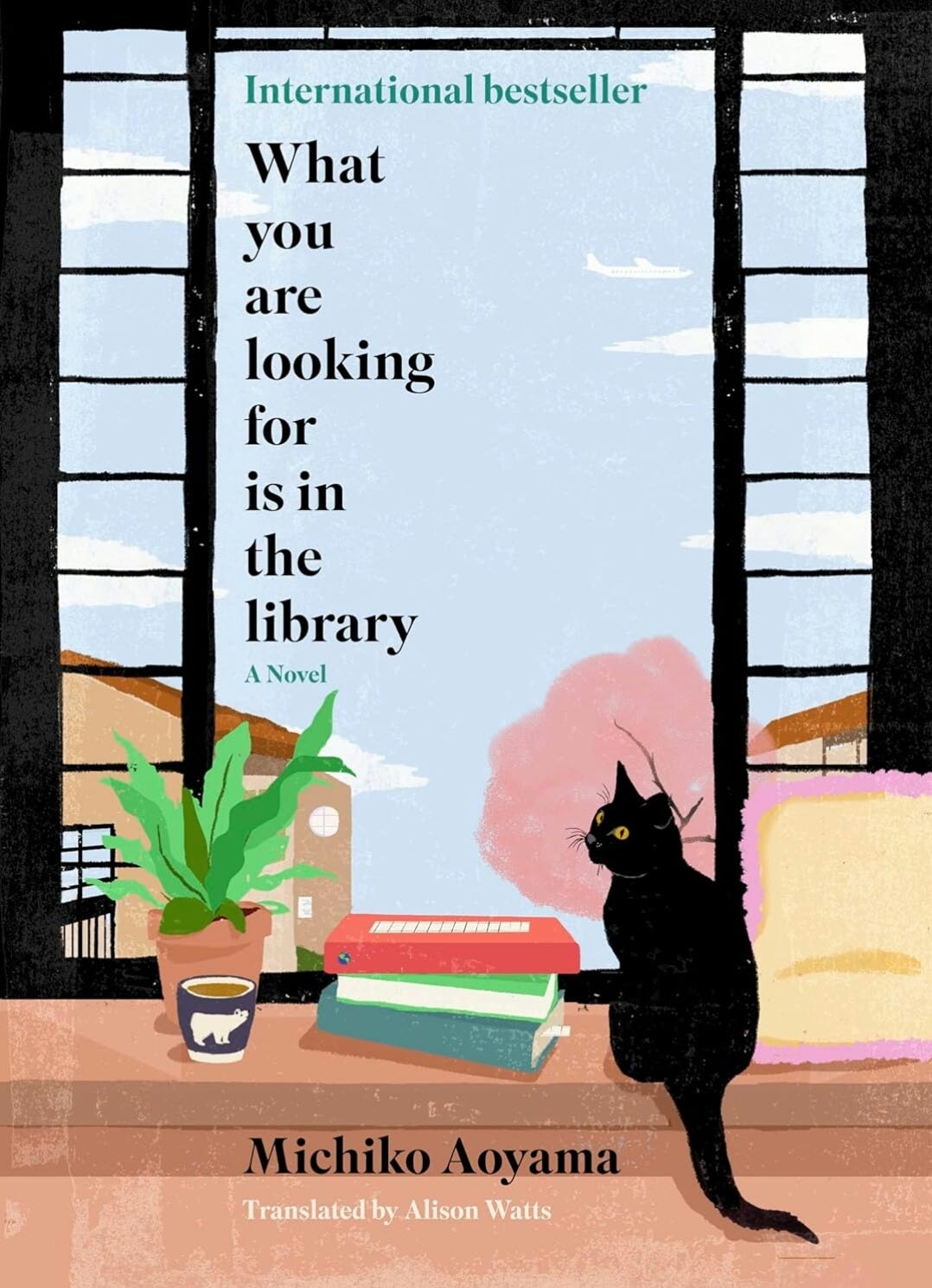

For now, I’m inviting you to read something along with me. Michiko Aoyama’s What You Are Looking For Is in the Library is short, delightful, easy to read, and well-written. Plus it’s about libraries (sort of) and it takes place in Japan. And, in my humble opinion, it very definitely has something in common with what Kierkegaard has to say about human beings.

Would you like to read and discuss it with me? We’ll meet online to chat about it on Thursday, February 27. That gives you plenty of time to get and read the book. Maybe you can borrow your copy from the library. *Wink*

Our word game this time has to do with “misanthropic,” because of course it does. The word’s root is the Greek anthrōpos, which means human being. Misanthropy is the hatred of human beings; philanthropy is the love of them.

Your job: make up another word that has anthrōpos as its root. Tell us what it means. Better yet, use it in a sentence.

This. Is. A. Good. Time. Try it!

And now, without further ado, your poem.

Seeing for a Moment I thought I was growing wings— it was a cocoon. I thought, now is the time to step into the fire— it was deep water. Eschatology is a word I learned as a child: the study of Last Things; facing my mirror—no longer young, the news—always of death, the dogs—rising from sleep and clamoring and howling, howling, nevertheless I see for a moment that's not it: it is the First Things. Word after word floats through the glass. Towards me. -Denise Levertov

It delights me no end to write to you. Thank you so much for reading.

With joy,

Rebecca

The opening sentence of The Sickness Unto Death. More sentences from Kierkegaard next time, I promise.

Beanthropy: the becoming of human beings 🙂

I got the book. :)