Dear Friends,

Do you play Wordle? But of course you do, because if fun can be had with words, then by gum, you’re having it.

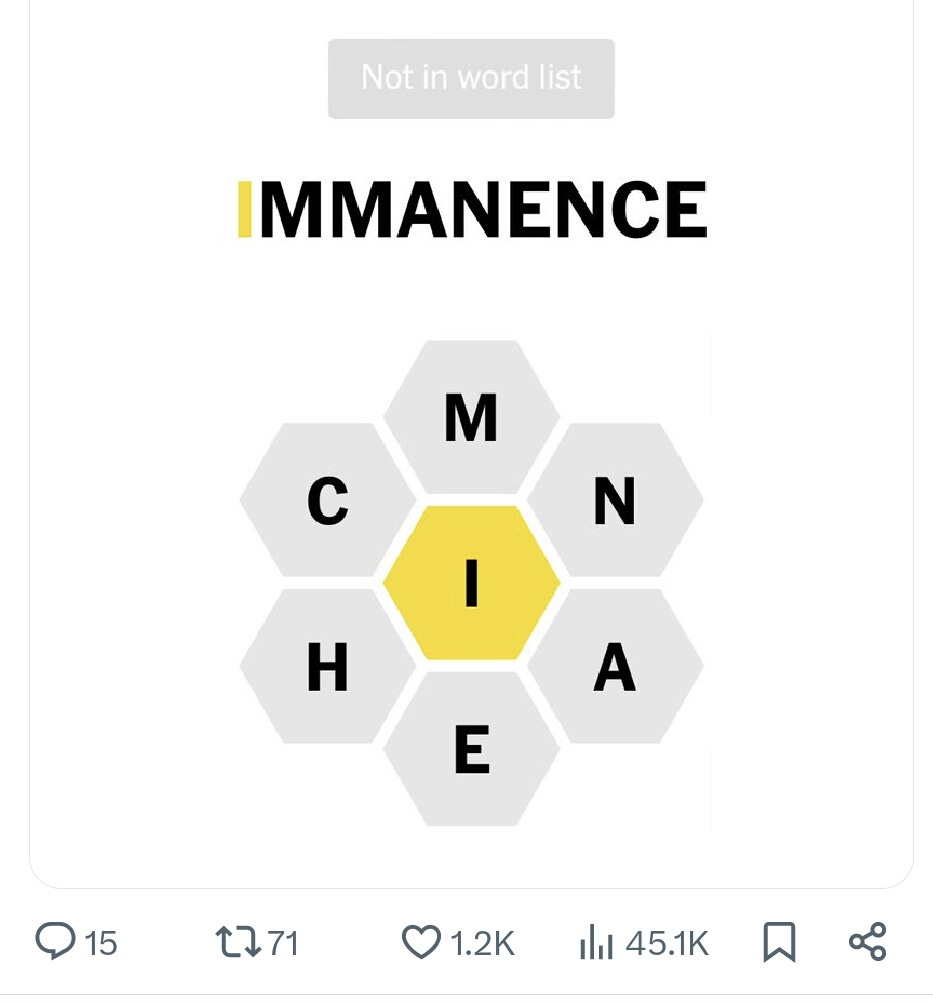

I play Wordle most days, and also Connections, the Mini-Crossword, and the Spelling Bee, pictured above, on The New York Times games app. Do you?

Good times. Vastly better times, in my opinion, than most other on-line options. But if I’m going to be on X for any time at all, I’ll enjoy whatever Fred Sanders has got going. He’s a theologian and professor of theology whose kind prose (kind as in clear) helped me wade through what were tricky ideas in my earliest weeks here. Other attributes: he doesn’t take himself seriously, he takes God very seriously, and he enjoys words, good grammar, great writing.

Everything to like.

Some of these came together recently in Dr. Sanders’ repost of Dr. Kadue’s post, in which she suggested that the games’ editors might lack some theological understanding. All the necessary letters were present and in the right place for her to play the word immanence, and the game’s response to this was “Not in word list.”

This little non-event inspired this very edition on my Substack.

More on that, but first, here’s the game for this week: Be first to respond by correctly defining (in an email to me) the following words:

immanence

imminence

eminence

Easy peasy. But note! Winning this game entails the following:

you must be correct in all your definitions,

you must be the first one to be correct in all your definitions, and

you must respond via email and NOT via the comments, lest (“lest”!) the game be ruined by someone giving it away.

The winning responder will be lauded in the very next issue of this very Substack.

Need I say it? No looking up the words! Despite our deep love for the dictionary, you know better than this.

And finally: Yes, I know, I know. “Eminence” is obviously different from the other two by virtue of pronunciation. To which I say: Not if you’re from the South. True southerners say all three of those words exactly the same way. As they do “pin” and “pen.”

But this is (or seems to be) a digression from the subtitle of this newsletter, “the ways we occupy space.” Never fear. That’s what’s next.

In an effort to understand God and all things related to God (and that there is a definition of theology), classical theologians (such as Thomas Aquinas, James Turretin, William of Ockham— you know, those guys) defined two types of beings: material (that’s us and other creatures with bodies) and immaterial (angels, God, human souls). And they distinguished different modes of those beings’ presence, or occupation of space. Here’s1 their view:

Created material beings can only be in one place at a time. We know this, no matter how we might wish otherwise. Yet we’re also composed of parts, and these parts can be in different places. This is why shrieks arise from your car’s backseat when Tommy’s knee creeps over the line. Janie insists that Tommy is now on “her side,” when in fact (Tommy is quick to point out), it’s only Tommy’s knee that’s encroaching. All the while, you, contending with traffic in the driver’s seat, are keenly aware that created material beings Tommy and Janie are wholly present in the back seat of your car. This is called circumscriptive presence: human beings are “circumscribed by and contained in the place in question.”2 In this case, all of you are circumscribed by your car.

Created spiritual creatures such as angels and human souls aren’t made of parts: they’re non-composite. As such, they can’t be circumscriptively present, with a part of them present in one place and another part elsewhere. Rather, wherever they are, they are wholly present. Your soul, for example, isn’t able to separate itself from your body, such that it can leave a car full of querulous children and take a walk in the park. At the same time, it’s not located in a single part of your body (as in your little finger). Rather, your soul is present throughout or entirely in your body. This is called definitive presence.

God, who alone is not created, is repletively present, meaning that he’s fully present everywhere at all times. He’s not composed of parts, thus he’s not circumscribed by place. And as spiritual being, he is wholly present. Ross Inman quotes Augustine,3 who said it this way:

“Yet he is not spread out in space like a mass such that in half of the body of the world there is half of him and half of him in the other half, being in that way whole in the whole. Rather, he is whole in the heavens alone and whole on the earth alone and whole in the heavens and in the earth, contained in no place, but whole everywhere in himself.”

That there is enough to think about for a long time.

We commonly think of God’s repletive presence as omnipresence, which is accurate. Theologians make a distinction between omnipresence and what they call divine immensity, but I won’t go into this here.

Rather, I’m writing today because of these words and what they mean and, most importantly, what they say about God: the world is replete with him.

A definition of replete: filled.

And so one might say that the world brims with him, that it teems with him, that it’s loaded or thick or overflowing with him. It’s awash with him, saturated, and abounding. The world is fraught, flush, crammed, lively, thronging with the presence of its Creator.

He is everywhere; there is nowhere that he is not.

Many of us (do you?) know it this way:

"Where can I go from your Spirit?

Where can I flee from your presence?

If I go up to the heavens, you are there;

if I make my bed in the depths, you are there.

If I rise on the wings of the dawn,

if I settle on the far side of the sea,

even there your hand will guide me,

your right hand will hold me fast." Psalm 139: 7-9I find this deeply comforting. I hope you do, too.

There’s more to be said about God’s repletive presence. Far, far more than I understand or am capable of saying. I’ll definitely say more next time (some bits I think I understand) but I’ve said enough for now.

So here’s your poem. You’ve earned it.

On the Origins of Things Everyone knows that the moon started out as a renegade fragment of the sun, a solar flare that fled that hellish furnace and congealed into a flat frozen pond suspended between the planets. But did you know that anger began as music, played too often and too loudly by drunken performers at weddings and garden parties? Or that turtles evolved from knuckles, ice from tears, and darkness from misunderstanding? As for the dominant thesis regarding the origin of love, I abstain from comment, nor will I allow myself to address the idea that dance began as a kiss, that happiness was an accidental import from Spain, that the ancient game of jump-the-fire gave rise to politics. But I will confess that I began as an astronaut-- a liking for bright flashes, vast distances, unreachable things, a hand stretched always toward the furthest limit-- and that my longing for you has not taken me very far from that original desire to inscribe a comet's orbit around the walls of our city, to gently stroke the surface of the stars. --Troy Jollimore

As ever, thank you so much for reading.

With Joy,

Rebecca

While the basic understanding summarized in this post might be considered common knowledge in theological studies, I had great help via Ross Inman’s “Retrieving Divine Immensity and Omnipresence,” in Arcadi and Turner, eds. T&T Clark Handbook of Analytic Theology, 127-140.

Inman, 130.

Augustine (2004) Letters 187, 4.11, trans R. Teske, ed. B. Ramsey, Hyde Park: New City Press.